Richard Feynman was a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who made significant contributions in quantum mechanics and particle physics. He pioneered quantum computing, introduced the concept of nanotechnology, and was a renowned lecturer at Cornell and Caltech.

Despite all of these accomplishments, Feynman thought of himself as just “an ordinary person who studied hard.” He believed anyone was capable of learning anything by putting enough effort—even complex physics subjects like quantum mechanics and electromagnetic fields.

There’s no miracle people. It just happens they got interested in this thing and they learned all this stuff. There’s just people.” – Richard Feynman*

But what made Richard Feynman Richard Feynman (according to him, at least) wasn’t innate intelligence but the systematic way in which he identified the things he didn’t know and then threw himself into understanding them inside and out.

Throughout his work and life, Feynman provided insights into his process for considering complex concepts in the world of physics and distilling knowledge and ideas with elegance and simplicity. Many of these observations about his learning process have been collected into what we now call “The Feynman Technique.”

This article will provide an overview of the Feynman Technique for learning and how you can apply it to continuously expand your knowledge and skill set. In short, Feynman will teach you not just how to learn but how to truly understand.

What Is the Feynman Technique for Learning?

“I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.” – Richard Feynman

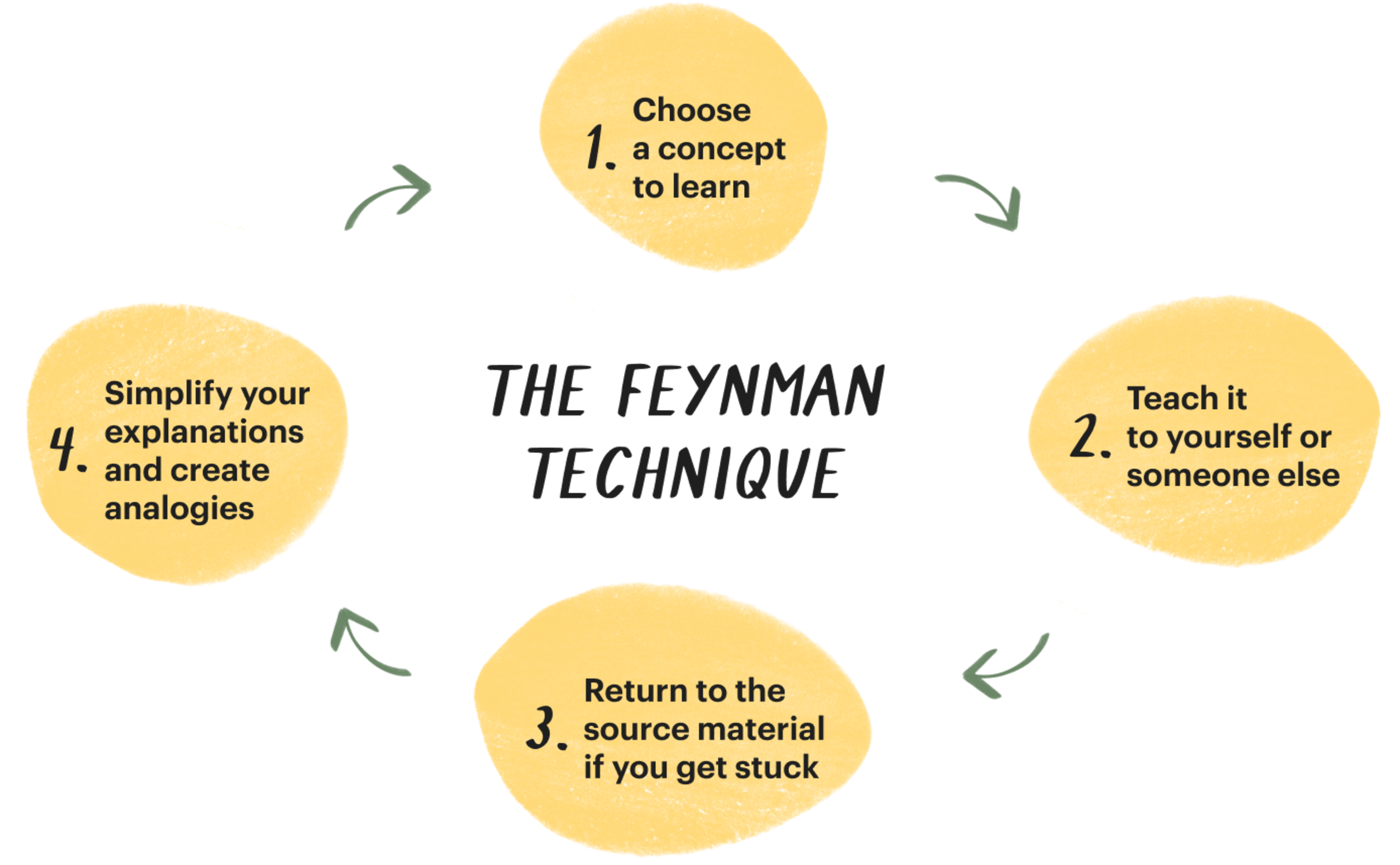

The Feynman Technique is a four-step process developed by Richard Feynman to learn any subject—no matter how hard or complex it is. This technique rejects memorizing facts without understanding their meaning and favors true comprehension through selection, research, writing, explaining, and refining.

Feynman’s biography, written by James Gleick, provides a host of clues into the famous nobel prize winning physicist’s learning process. Here’s just one:

“In preparing for his oral qualifying examination, a rite of passage for every graduate student, he chose not to study the outlines of known physics. Instead he went up to MIT, where he could be alone, and opened a fresh notebook. On the title page he wrote: Notebook Of Things I Don’t Know About. For the first but not the last time he reorganized his knowledge. He worked for weeks at disassembling each branch of physics, oiling the parts, and putting them back together, looking all the while for the raw edges and inconsistencies. He tried to find the essential kernels of each subject. When he was done he had a notebook of which he was especially proud.”

Feynman believed that learning a new skill or concept should be an active process of "trial and error, discovery, free inquiry." He held that if you couldn't explain something clearly and simply it was because you didn't understand it well enough.

The 4 Steps of the Feynman Technique

Feynman’s technique condenses all his philosophies of active learning, simplification, teaching, identifying knowledge gaps, and iterative refinement in four simple steps.

A graphic that shows the 4 stages of the Feynman Technique

Choose a concept to learn. Select a subject or branch of knowledge you’re interested in learning. Then, write it at the top of a blank page in a notebook. If you have a syllabus or a table of contents from a book for that specific subject, choose a concept to start learning. If not, start with foundational concepts and add more complexity as you go.

Teach it to yourself or someone else. Write everything you know about a concept as if you were explaining it to yourself. Writing without transcribing forces you to understand rather than memorize. If possible, teach it to someone else.

Return to the source material if you get stuck. Go back to whatever you’re learning from—a book, lecture notes, podcast—and fill the gaps in your knowledge. Return to step two and repeat until the concept is clear.

Simplify your explanations and create analogies. Streamline your notes and explanation, further clarifying the topic until it seems obvious. Additionally, think of analogies that feel intuitive.

When you use the Feynman method, you learn with intention. Breaking down topics into digestible chunks and explaining them helps you identify gaps in your knowledge. This creates new neural pathways in your brain, which makes connecting ideas and concepts easier.

Think of it as building a tower. Every concept is a brick, as you understand and explain each one, you keep adding them to the tower. With a solid foundation in place, you make stronger connections which improves your memory and reinforces learning. Not to mention that building up your knowledge becomes easier.

How the Feynman Technique Works

“I couldn’t reduce it to the freshman level. That means we really don’t understand it.” – Richard Feynman

Often, we don’t realize we don’t understand something until it’s too late.

Maybe you’re facing down a question on an exam. Or someone asks you to explain a topic you thought you understood. And suddenly, your mind goes blank. When you’re asked to demonstrate your knowledge outside your own head, you realize you knew a lot less than you thought.

The Feynman study technique doesn’t let us fool ourselves into thinking we’re masters of a subject when we’re really amateurs. Each step of the process forces us to confront what we don’t know, engage directly with the material, and clarify our understanding.

1. Choose a Concept to Learn

Selecting a concept to study compels you to be intentional about what you don’t know. It also forces you to choose a topic that’s small enough that it could reasonably fit onto one or two pages.

Pick up a fresh book or digital document and jot down the concepts or topics you want to learn. If your knowledge about a topic is minimal, start with foundational concepts and gradually move into more complex ones. Also, remember to focus on one concept at a time, once you learn it, you can move onto the next.

Branch of Study | Topics to Choose |

Front-End Development | Optimizing SVG, Web Forms 2.0, conditional statements, css flexbox |

Product Design | Attribute listing, beta prototypes, accessible typography, journey mapping |

Evolutionary Science | Negative selection, heritability, phenotypes, random mutation |

Microeconomics | Elasticity, oligopolies, allocative efficiency, marginal product |

Psychology | Parasocial relationships, WEIRD, group polarization, social loafing |

Calculus | Definite integral, right-endpoint approximation, exponential decay model, inverse trigonometric functions |

Why this step works:

You face what you don’t know. By writing a topic down on a blank page, you acknowledge you’re starting from scratch or at least filling in some blanks. This promotes a curiosity mindset, which helps you identify areas that need more focus.

You start with an open mind. When you leave aside preconceived notions, you’re able to comprehend new concepts deeply. You’re trying to understand rather than proving yourself right.

You need to be specific. Given the accumulated knowledge in the universe, most of us know nothing about most things! Writing down explicitly what you don’t know provides you with a starting point.

You start small. You really only have a page (or a few) to fill up with information. You can’t fit everything there is to know about “Evolutionary Science,” “Microeconomics,” or “Psychology” on a page. Instead, work on smaller, more defined concepts or what might reliably be found on a midterm or final exam.

Whenever you start learning a new concept, remember to pick one that can be covered in one or two study sessions. You don’t want to spend hours with no end trying to understand a new concept. This can lead to you feeling overwhelmed or burned out.

2. Explain it to yourself or teach it to someone else

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” – Richard Feynman

A classic learning mistake is reading an article or textbook and considering our learning complete. In reality, reading isn’t understanding. We might even take notes, essentially transcribing a resource’s sentences into our notebooks. Then we nod to ourselves, thinking we’ve grasped a subject. After all, we’ve taken notes.

But true understanding requires a more active process like teaching. According to The Learning Pyramid, you retain 10% of what you read but an overwhelming 90% of what you teach to others.

So start by teaching yourself. Either by writing a summary in your own words (without looking at your notes) or explaining the concept out loud. This will force you to connect and articulate the ideas.

Then, when you feel like you can transmit the concept with ease, teach other people. Teaching initiates a feedback loop where critique or questions can help us learn and sharpen our thinking. Moreover, sharing ideas with other people may help you learn new perspectives and come up with more questions.

Difficulty Level | Tactics to Teach Yourself or Others |

! | Write topic summaries and notes Teach yourself aloud without your notes Spark debates with friends or colleagues |

!! | Write tweet threads Answer questions on Quora Write a Good Reads review |

!!! | Speak at a conference Volunteer as a tutor Produce a podcast Start a blog |

Why this step works:

It makes it harder to trick yourself. When you have to truly explain something, whether through writing or aloud, you encounter the holes in your reasoning and the white spaces in your knowledge. Think of writing and teaching as a process to obtain understanding, not something you do once you already understand.

It’s even harder to trick others. If an explanation you’re providing doesn’t make sense, they’ll often tell you or you can pick up cues like blank stares. As a test, ask them to repeat what you taught them in their own words. If they can’t do this, your explanation is too complex––simplify it and use plain language.

You build confidence. When you truly understand something, it clicks. You can explain it forward and backward, pointing out exceptions and spotting logical inconsistencies. This builds confidence and pushes you to tackle even more challenging subjects, knowing you have a solid framework for learning.

You reinforce your own learning. Teaching others means you have to think about how to introduce the topic and make it easy to understand. Not only do you have to recall information and present it, you have to organize it coherently. And when the person you’re teaching doesn’t understand, you have to re-organize it and distill it into more simple concepts.

At the beginning you may think this step is annoying. Why should you repeat to others what you already taught to yourself? Shouldn't you use this time to move on to the next concept? The thing is, this repetition strengthens your neural connections and improves long-term retention. Also, when people ask questions, and you go back and forth, you find more gaps in your knowledge.

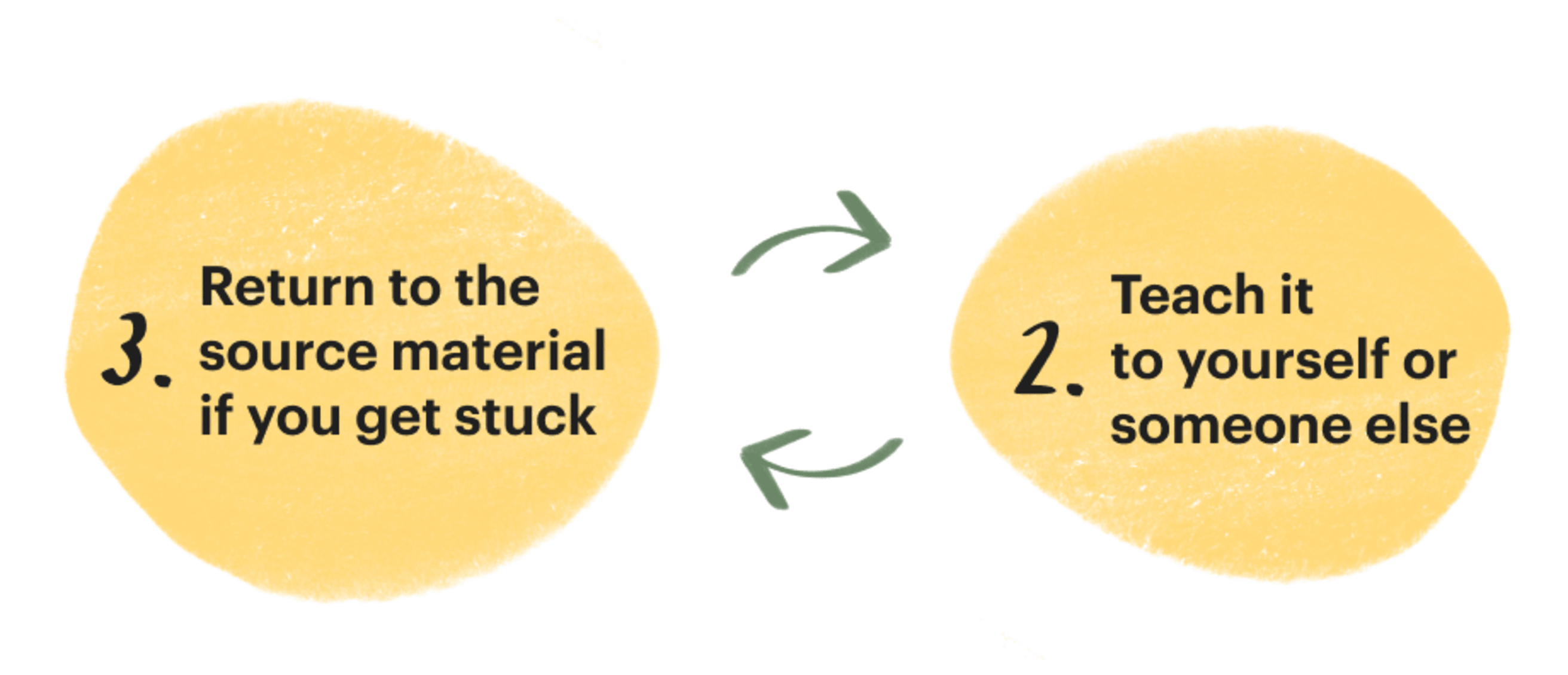

3. Return to the source material if you get stuck

Learning should be iterative. Often, learning something challenging takes several attempts. With the Feynman learning technique, returning to the source material is an explicit part of the learning process. When gaps in our knowledge arise and our explanations aren’t quite right, revisiting our primary and secondary sources can help solidify what we’re learning.

Getting it right will likely take several iterations. That’s a good thing! The more you refine your explanations, the more your understanding will deepen.

Why this step works:

Learning becomes an iterative process. Rather than viewing learning as one-and-done, this step gives you permission to continuously refresh your knowledge.

You’re actively engaged. Using sources to polish our own explanations and models is an active process. When we learn passively, committing details to memory is more challenging. When we’re actively part of creating our own summaries and reasoning, drawing intentionally from original information to fill our blind spots, we can more readily commit knowledge to our long-term memory.

You expand your knowledge base. Paradoxically, the more we learn, the more our capacity to learn increases. Looking through a chapter of a textbook might feel like a different language the first time around. The second time it becomes more clear. The third time, with a strong base already, we pick up nuances we couldn’t have possibly seen before.

It broadens “the big picture.” When you revisit material a third or fourth time, you start questioning more things. You start to see the context behind the concept, which allows you to understand how different pieces of information fit in the big picture.

It’s normal to use just one source of knowledge when you first start learning. However, as you feel more comfortable with a concept, consulting different source materials like books, online learning sites, videos, or articles will help you have a more rounded understanding.

4. Simplify your explanations and create your own analogies

Every field of study has its own specialized terms. While it may be important to know them, it’s also important to not confuse knowing jargon with knowing concepts. The Feynman Technique for studying involves simplifying our initial explanations and refining our understanding through simple analogies.

Why this step works:

Simplicity is a proxy for understanding. It’s easy enough to commit terms to memory, and repeat them back when prompted. But memorization isn’t understanding. When we can’t rely on big words that make us sound smart, we have to distill what we truly know into the most basic form. This is where true understanding takes place.

Analogies are easier to recall and explain. When you understand a challenging concept, analogies allow you to create a shorthand for recalling it quickly and explaining it to others clearly. Learning material often provides ready-made analogies for us. For example, we all probably have “the mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell” burned into our collective memories. However, pushing ourselves to create our own analogies is even more powerful than regurgitating a borrowed one that we may not actually understand.

Facilitates communication. Simplifying your explanations or creating your own analogies helps you better communicate complex ideas to others. Moreover, you can make your analogies relevant to the context and audience. It’s not the same as explaining what "quantum entanglement" is to high school students as it is to PhD graduates.

Promotes creativity and problem-solving. When you create your own analogies, you understand the core components of the concept and their relationship. Which makes it easy to break down problems into components and relationships in real life, too. You start approaching problems from different angles and come up with better solutions.

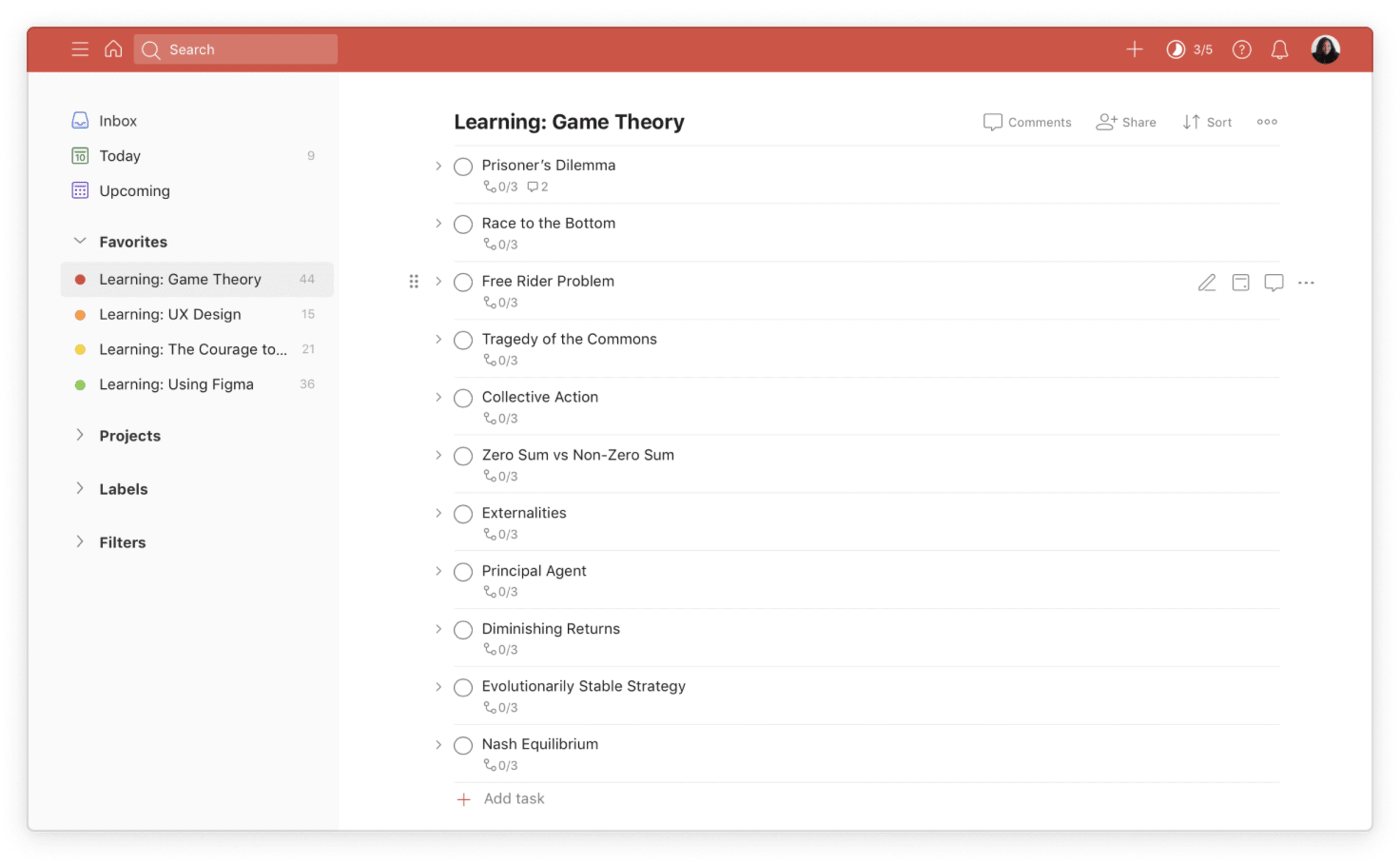

Using the Feynman Technique With Todoist

While using your curiosity as a compass to choose what you learn is a great start, setting up a plan for when and how you learn is a more intentional way of pursuing knowledge.

Use Todoist to schedule when you’ll learn and add the steps of the Feynman as tasks. Here’s an example:

Create a Todoist project for the “Branch of Study” you’re focusing on. This could be any number of things like a broad field in the sciences, a particular self-development book, or a software tool you want to develop expert proficiency in.

Generate a list of tasks based on the topics you’ll learn. Choose the concepts or topics relevant to that branch of knowledge and add them as Todoist tasks in the project you created in the previous step. If you know the topics you need to learn, for example, if you have a syllabus or a table of contents for a book, add them as tasks all at once. If not, add individual topics as you go.

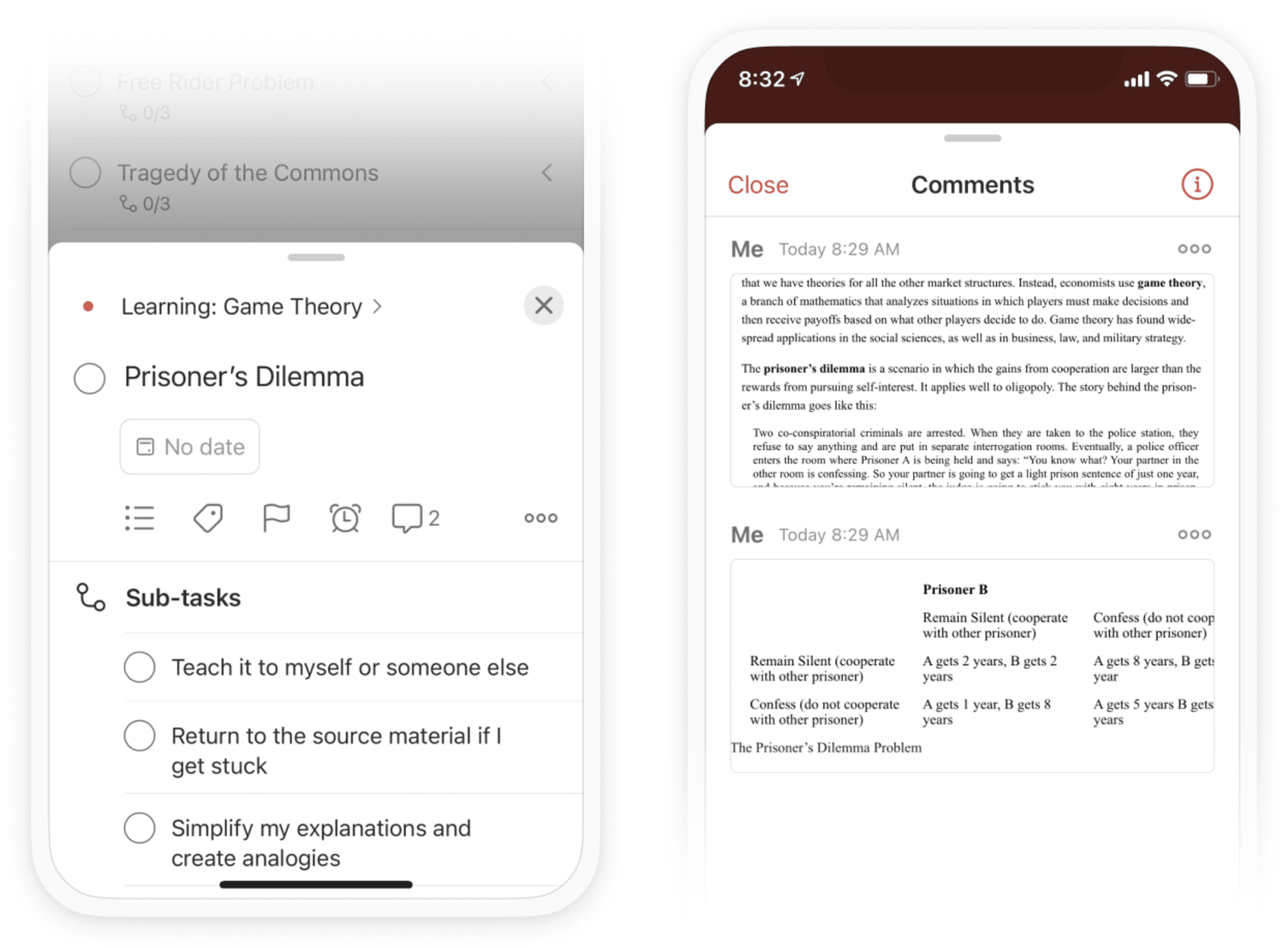

For each task, add steps 2-4 of the Feynman Technique as subtasks. Add “Teach it to myself or someone else”, “Return to the source material if I get stuck”, and “Simplify my explanations and create analogies” as subtasks to your main tasks. Add due dates to each subtask to keep the momentum going and create accountability in your learning process.

Use the comments to add relevant links, notes to self, and source material. Tasks comments can be helpful to keep track of source materials, or jot down ideas and theories on the go before you transfer them to your notebook.

Add notes and references to your task comments

Note

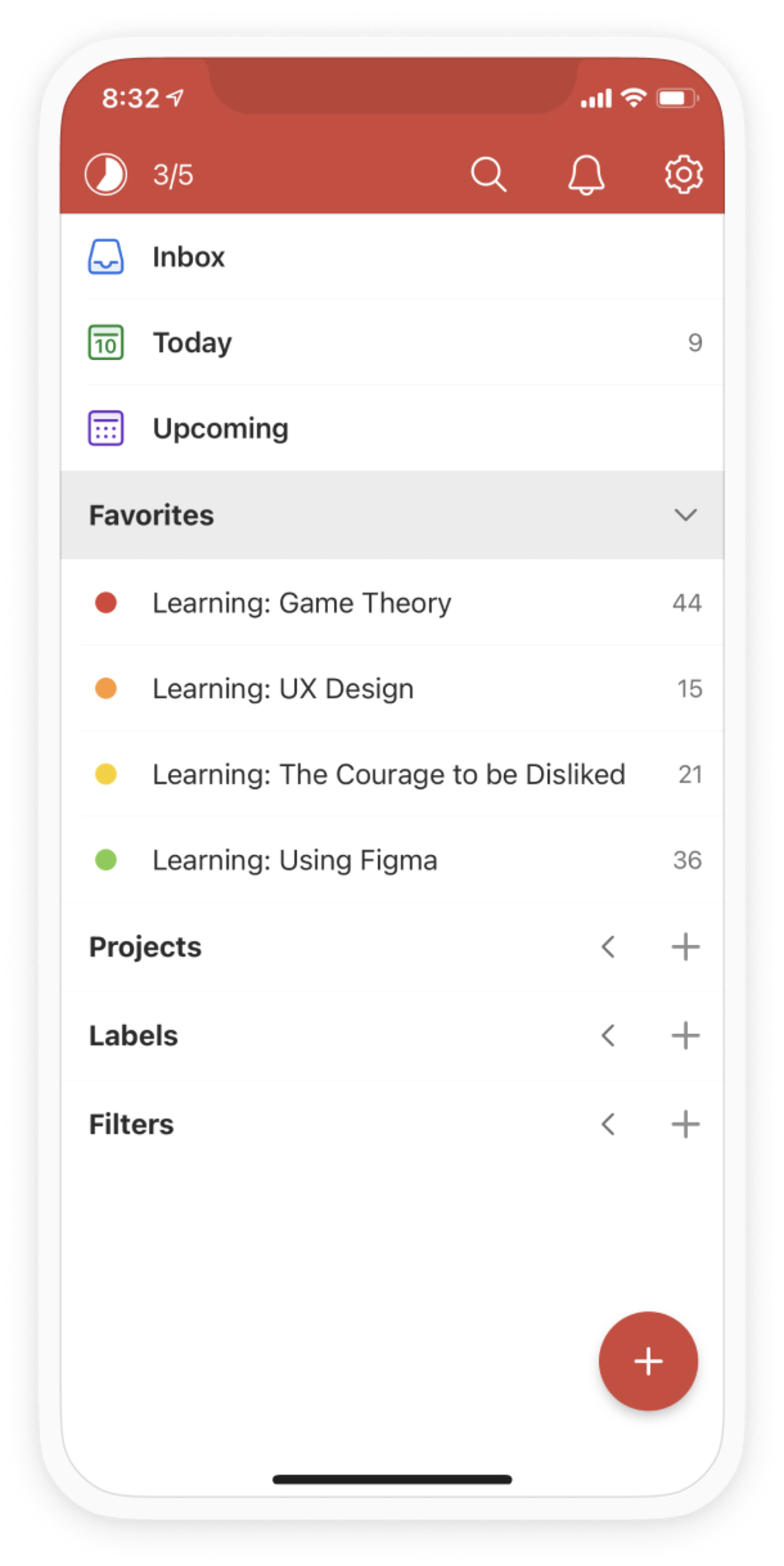

Product Tip: Keep your learning and education top of mind. Pin your Learning Projects as Todoist Favorites for easy access.

Add all your learning projects to your Todoist Favorites

By systemizing your learning in a task manager, you always have a digital space to review what you’ve learned and check in on your progress. Instead of simply being a passive process, learning can become a part of our regular routines.

In Tyler Cowen’s Average is Over, the renowned economist notes that technological advances are driving us towards a future of work where, “lacking the right training means being shut out of opportunities like never before.”

When describing the role of education in future economies, Cowen argues that the person who finds success will increasingly be the one “who sits down and actually starts trying to master the material.”

Now, more than ever, it’s important to adopt the mindset of a life-long learner.

Learning new skills and information takes time, patience, and humility. Starting with a blank page forces you to confront what you don’t know head-on. From there, you only need a pen, learning resources, and the willingness to embark on a continuous learning quest.